Books I Read This Month: October 2024

Bill Zehme + Mike Thomas • László Krasznahorkai • Helen Phillips

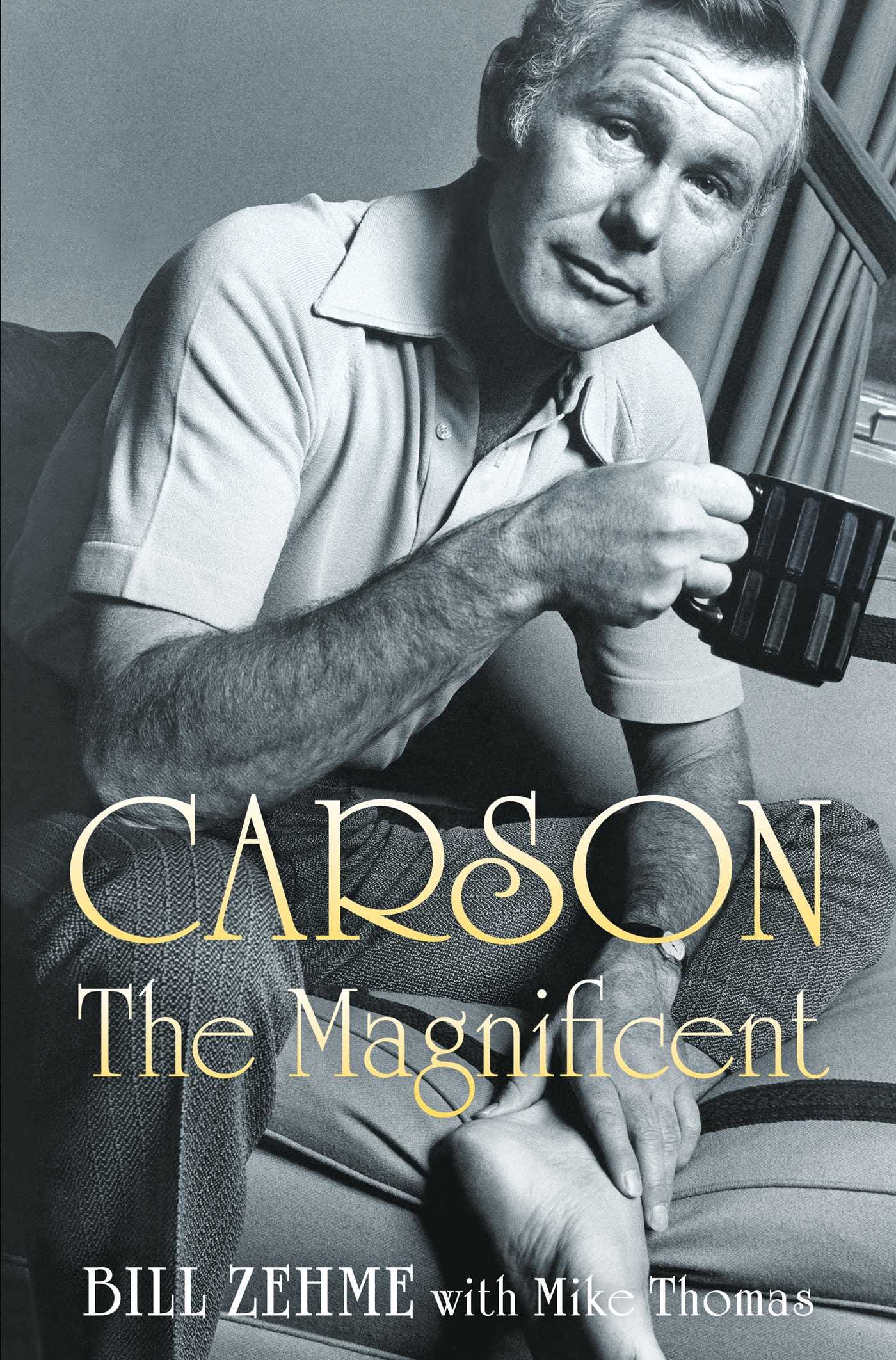

Carson the Magnificent (Bill Zehme with Mike Thomas)

A Boswell to the big-deal men of a bygone era, the biographer and magazine writer Bill Zehme was often too much of a stan to be a great chronicler. He profiled the talented white guys he idolized who lorded over the postwar culture—Hugh Hefner, Frank Sinatra, Woody Allen, etc.—an A-list that doubled as a rogues’ gallery. His flawed subjects and their families spoke glowingly of the scribe, which should be your first hint that he was nice but maybe not the most rigorous journalist. You needn’t be a trash-sniffing sensationalist like Kitty Kelley or Albert Goldman to prove your bona fides, but maintaining some distance is an asset in the trade. The title of Carson the Magnificent, the late Zehme’s posthumous bio of longtime Tonight Show host Johnny Carson, more than suggests that the book has a strong bias. The author unsurprisingly simps for the gifted star he worshiped, hyperbolically lauding his “long, heroic reign,” but he soft-pedals, to a shocking degree, the worst of Carson’s out-of-studio behavior.

One of the most famous and beloved American public figures in the second half of the twentieth century, Carson plopped down into the host chair of the late-night NBC program on October 1, 1962, and spent the next three decades putting the country peacefully to sleep, remaining a constant presence through six Presidential Administrations, the Vietnam War, Watergate, you name it. Located in NYC for its first decade, the show was frequently a booze-fueled free-for-all deemed acceptable even before that decade’s tumultuous cultural shift loosened standards and practices, primarily because of the host’s boyish, devilish charm. (One night in the 1960s, during a star-crossed show, Carson gave up hope and performed a spontaneous striptease act, getting naked from the waist up. His longtime sidekick, Ed McMahon, and the all-male panel subsequently got topless.) Carson could effortlessly tell prepared monologue jokes with exquisite timing, ad-lib brilliantly when bantering with guests, and turn any failed punchline into a laugh at his own expense, immediately defusing bombs. He was a supremely disciplined entertainer, but he was out of control and chaotic in pretty much every other facet of his life: an alcoholic, a reckless businessman, an indifferent father, and, worst of all, a domestic abuser.

Zehme’s handling of the latter failing, spousal abuse, is beyond egregious. He describes his favorite entertainer drunkenly battering his first wife, Jody, this way: “Occasionally he would wake the next day to discover that some such havoc had bruised the flesh of his sons’ mother.” The passive tone removes agency from Carson for his horrific behavior, which is stomach-turning, especially since more than one of the serial groom’s wives described being frightened for their lives during these bouts of terror. Zehme stresses that Carson experienced “Jekyll/Hyde switchovers” during his blackout drinking binges as if the guy who gave us El Mouldo couldn’t possibly be the one responsible for the menacing violence—it must be his evil twin. It’s the rationalization of someone unable to accept that a celebrity they adored from afar could be horrible up close.

“My feelings about my dad are quite mixed.”

Carson, who possessed some of Groucho Marx’s leering wit and Danny Kaye’s agile physicality, was usually lightness before the cameras, the only place he truly felt comfortable—but Zehme doesn’t mention that the host’s unpleasantness reared up occasionally in front of the nation. There he was in the late 1980s, making misogynistic cracks when interviewing the young cartoonist Cathy Guisewite, who’d smuggled a new female perspective into the funny pages with her progressive/regressive namesake strip. And that was him in 1982 belittling one of his sons before millions. His youngest child, Cory, a shy, sad-looking 29-year-old man, appeared as a guest one night in 1982, capably if unremarkably playing an instrumental on guitar. After the performance, the host walked over to his son, who could barely make eye contact with his famous father, and perfunctorily invited him to come back again sometime, using the insincere show-biz parlance he would employ with any other guest. The son deadpanned, “When?” It got a laugh. Instead of letting his kid briefly enjoy the spotlight, Carson went for the jugular. I don’t recall the exact wording, but he said something like, “Maybe when you learn another song.” It was the most withering thing to watch. Decades later, in 2005, Cory began an email to Zehme with this sentence: “My feelings about my dad are quite mixed.” No surprise.

Zehme scored the only post-retirement interview Carson did, which ran in Esquire in 2002, but his bio doesn’t offer any enlightening new information. (Chicago Sun-Times arts journalist Mike Thomas finished the volume for Zehme, who struggled to complete the book before being diagnosed with colorectal cancer in the 2010s; he died in 2023.) We’re presented with the same narrative and details any Carson watcher has heard a million times: The host played the role of everybody’s favorite son, brother, husband, or lover when acting as America’s First Host, but he was a profoundly private and aloof figure when the “ON AIR” sign went dark. As McMahon diplomatically stated during their run together, “Johnny packs a tight suitcase.”

Zehme ascribes part of this vanishing act to Carson’s lifelong love of magic. A Nebraska kid who dreamed of becoming a professional magus, he dubbed himself the “Great Carsoni” after his parents presented him with some of the rudiments of the trade. He practiced with a monomania, preparing to reveal to audiences what he wanted them to know about a trick while hiding any revealing details. He carried this pattern with him in all parts of his life. Zehme belabors the point, but there’s probably something to his theory. Even at the height of his fame, Carson would visit the Magic Castle in Los Angeles, a clubhouse for those taken by legerdemain, with fellow A-listers, including Orson Welles and Steve Martin.

A solid if familiar telling of the Carson narrative is interrupted periodically by embarrassing hero worship.

What’s perplexing, though, is that the author believes something is astounding about the host’s semi-reclusive stature when offstage—the host was the “ultimate Interior Man,” he asserts—amazed that Carson desired a spotlight some of the time but mostly cherished solitude. Zehme isn’t the first critic to be perplexed by this supposedly ineffable dichotomy, and you have to assume anyone so baffled never took Psychology 101. It’s pretty simple: Carson was an introvert. He could be the center of attention, sharing himself for a while, but he required lots of downtime to recuperate. If you were a close associate and ran your mouth about his personal life in a way that he felt was intrusive, you got permanently planted in the cornfield. Carson is far from the only one with this personality type—it’s neither rare nor fascinating.

A solid if familiar telling of the Carson narrative is periodically interrupted by embarrassing hero worship. “Johnny Carson saved my life” quotes are on display, and one eye-popping section recalls other monumental historical events that occurred on October 1, the day of Carson’s inaugural Tonight Show. You might assume the author is joking when he mentions the host’s debut show alongside the birth of Henry III (October 1, 1207), Napoleon overtaking Belgium (October 1, 1795), and Henry Ford introducing the first Model T (October 1, 1908). But, no, he’s seriously comparing Carson’s ascent with these world-shaping events.

At his best, Carson entertained people and made them feel less alone, which is not nothing. It’s easy to miss the host’s presence and yearn for the culture he used to inhabit, an imperfect one that was much more centralized. In his final monologue on May 22, 1992, Carson noted that the world population increased by 2.4 billion during his stint as Tonight Show host. He joked that half those people would soon host a late-night TV program. He was talking about all the Carson clones and alternatives turning up on broadcast and cable but was unintentionally prophetic. His final sign-off occurred three years after the introduction of the World Wide Web, and the narrative in the U.S. and elsewhere would shortly begin to splinter. Social media started that same decade, and podcasting during the next one. These developments were both good and bad. Carson and his overwhelmingly white staff were myopic, never once booking a rapper (unless you count Pigmeat Markham) during hip hop’s mind-blowing ascent. There needed to be a more diverse assortment of quality chat shows. That’s not only what the new technologies delivered, however.

It was the apex of the Space Race, which seeded the heavens with satellites, making the Internet possible and creating an infinite number of thrones for kings of comedy everywhere.

Carson and McMahon were seated in the VIP stand on July 16, 1969, to view the Apollo 11 launch at the Kennedy Space Center on Merritt Island, Florida. It was a sweltering morning, and those in attendance complained that there weren’t enough iced drinks at the refreshment stands to keep them cool. The rocket lifted off cleanly at 9:32 a.m. and reached its destination 75 hours later. It was the apex of the Space Race, the Cold War competition that began seeding the skies with satellites, ultimately making the Internet possible and creating an infinite number of thrones for kings of comedy everywhere. There were no more pesky middlemen or censors—just an endless array of microphones. And if the pseudoscience the edgelord podcasters would eventually sell was more popular than the actual science that captivated Carson, that was the price of freedom.

Fifty-five years after Carson watched the Apollo 11 mission go off without a hitch, Joe Rogan, the podcaster who’s the most popular American talk-show host of this era, is unconvinced the moon landing occurred, prone as he is to all manner of conspiracy theories, continually dispensing dangerous misinformation about science, health, politics, and race. He’s a mark for pretty much any outré theory, given his lack of critical thinking skills. Just before I started writing this review, there was a report online about Rogan spreading Kremlin propaganda, confirming his status as one of the most useful “useful idiots” ever. A slew of simpatico men—comics, kooks, kickboxers, and technologists—joined his orbit during the last 15 years, doing their best to promote vaccine conspiracy theories and enable an openly fascist politician to return to the White House. Carson was there in 1969 to watch the beginning of a space journey that stretched 244,000 miles into the sky, and the new tools such journeys enabled have allowed us to fall from the stars.•

Herscht 07769 (László Krasznahorkai)

A little knowledge is dangerous, and Florian Herscht possesses just that amount. A towering teenager employed as a graffiti cleaner in a small burg in former East Germany, Florian is a pawn given to kingly thoughts. He emerges just before the pandemic from an adult education course in particle physics with a misunderstanding of principles, convinced he’s detected an urgent problem: the inevitable disappearance of reality itself! The Thuringian behemoth believes that “due to a diabolical breaking of the symmetry in the usually balanced emergence of particles and antiparticles, there suddenly arise, in one horrific moment, one surplus antiparticle, and while the one billion particles and one billion antiparticles are busy annihilating each other, and the well-known one billion photons are floating away, the remaining single surplus article could be creating a new reality, an anti-universe.” It’s a conspiracy theory of the cosmic kind. He embarks on a one-sided correspondence with Chancellor Angela Merkel, a scientist, and the nation’s leader, encouraging her to convene the UN Security Council before all is lost. When his missives go ignored—bureaucracy being bureaucracy—he travels to Willy-Brandt-Straße 1 in Berlin to try to pay her an in-person visit.

Such is the opening salvo of the Hungarian literary auteur László Krasznahorkai’s latest novel, a 2021 work newly available in English translation, that runs amok. Herscht 07769 is a political, psychological, and experimental novel and a massively violent thriller. The jaw-dropper, stylistically, is that the ever-innovative author, who’s been pushing formal boundaries since publishing Satantango in 1985, wrote the entire work as a single run-on sentence, a self-imposed obstruction that miraculously isn’t an impediment but instead propels the novel to stretch and grow wildly as matter did after the Big Bang. A story about nationalism and violence spiking in a declining, depressing part of Germany, it is to the tail end of the Merkel Era what Alfred Döblin’s 1929 masterpiece, Berlin Alexanderplatz, is to the Weimar Republic.

Florian’s employer in the graffiti-removal business, a neo-Nazi brute only referred to as “the Boss,” is forever slapping, punching, and insulting his enigmatic charge, whom he plucked from a children’s home, even though his enormous underling could crush him with his bare hands. The Boss, however, does define Florian accurately: “On the one hand he’s a genius, but on the other, the child is off his rocker.” The neighbors like the “gentle and shame-faced” Florian, believing him a good soul if an odd duck. They encourage him to break away from the heinous Boss. But Florian is loyal to the hyperviolent honcho as a stray cur can be to whatever master takes it in, even if it sometimes receives the business end of a boot.

“The apocalypse is the natural state of life,” Florian warns the Chancellor, “the world, the universe, and of the Something, the apocalypse is now.”

When the workers at the post office realize Florian is writing to Merkel, they respond with bemusement that he could believe that anyone important in Berlin cares about their backwater. They see themselves as having been forgotten after the Wall came down. “So much for the great unification, fundamentally nothing had changed, because fundamentally nothing ever changes,” is how one villager sums it up. If they could read the letter they might be worried that their neighbor is more Dostoevskian than dodo. “The apocalypse is the natural state of life,” Florian warns the Chancellor, “the world, the universe, and of the Something, the apocalypse is now.” His ill-conceived attempt to get close to her in Berlin results in a visit by her security detail. It’s concerning, but it’s also just Florian being Florian. The townsfolk have more serious problems as the pandemic reaches their community, and a series of strange and violent events stun the locals.

The elderly Adrian Kohler, the teacher of Florian’s physics course, who also runs a personal weather station to keep himself busy, disappears suddenly. No one knows of the whereabouts of the esteemed Herr Doktor. Someone is graffitiing statues of Johann Sebastian Bach with the tag “WOLF HEAD,” enraging the Boss, who reveres the composer above all countrymen, even Hitler. “Bach was the German character expressed in music,” he says, threatening death for the vandals. (He sponsors a piss-poor community symphony that can’t even approach the Brandenburg Concertos no matter how often they practice.) Herr and Frau Ringer are mauled and nearly killed in a wolf attack, their flesh bitten and scratched open. Authorities are baffled because wolves have never been spotted in the area and shy away from humans who don’t provoke them. Herr Ringer is an outspoken anti-Nazi and has accused the Boss of staging the Bach graffiti outbreak, so is he being targeted? Making things more suspicious is that the Boss shows up to shoot and kill the wolf. Soon after, one of the Boss’s stooges rapes a Moroccan immigrant.

Then the explosions begin. Bombs blow up a gas station, among other targets, and the frayed bandage holding the community together is ripped from the flesh. “This is how it’s going to be: women raped, explosions, wolves sent into our midst, that’s where we are now,” says one of the fearful residents to his neighbors. Streets are soon empty, and businesses close their doors. The Boss, a person of interest in multiple investigations, gives Florian a Nokia phone and instructs him to lie and tell anyone who asks that he calls his employer at home five times each night, giving him an alibi. Florian, usually serene, begins angrily arguing with anyone who makes accusations about the Boss behind his back—but he seems to be arguing with his conscience. A video accidentally left on the phone, however, clarifies matters.

What follows is a storm of dizzying violence, as whodunits are solved, and a blood-soaked thriller—think Cormac McCarthy at his most bleak and savage. To say any more would give away too much. At one point, a key townsperson suddenly stops speaking, with no explanation provided. The character, it’s said, is “apathetic, like someone who was indifferent to everything.” In less obvious ways, the village loses its voice, the locals becoming a loosely affiliated group more than a community, a people hollowed out by shock, hatred, and neglect.•

Hum (Helen Phillips)

Early in Helen Phillips’s speculative 2024 novel, six-year-old Sy screams in horror the first time he sees his mother after her face-altering surgery. She hasn’t had a vanity cosmetic procedure like an eyelid tuck or chin implant go awry. May has undergone an operation to marginally modify her features, working as a guinea pig for a tech startup aiming to improve ubiquitous facial recognition systems. She and her family desperately need the paycheck since she was deemed redundant in her job developing the communication abilities of AI, the system quickly becoming more sophisticated in linguistics than the carbon-based trainers. Her husband, Jem, an underemployed freelance laborer, isn’t getting much gig work beyond emptying mouse traps for homeowners. Rent is past due, the bills are piling up, so she accepts a deposit in her account in return for allowing a humanoid robot, a “hum,” to glide a needle across her cheeks and brow, making subtle modifications that will force the systems to learn to re-identify her. May’s visage only looks slightly different in the aftermath. Still, the reshaping has put her in Uncanny Valley territory with family and friends, and her small son runs away in terror, burying himself beneath couch cushions.

To be fair to the robotic surgeon, May’s children didn’t care much for her before the procedure, even though she appears to be a loving, concerned parent. They constantly rebuff her affectionate overtures and call her names. “Are you actually an evil person?” the boy asks her. “You look creepy,” her eight-year-old daughter, Lu, tells her when she spies her mother bathed in the light from her phone. May challenges them to staring contests, hoping the eye contact will create a bond. Sy and Lu prefer to avoid Mom’s gaze and zip themselves inside their wooms—egg-like isolation pods with screens full of entertainment. They’re not only being bratty; they feel closer to the AI they’ve grown up with that can anticipate their needs, especially the toy bunny/computer that all children wear on their wrists. Even in the solitude of wooms, the state is watching, and corporations are harvesting information. “Do I have permission to access?” they ask politely, but there’s always some punitive measure should you refuse, an extra fee or unfortunate inconvenience.

It's not clear how far in the future Phillips has set her story, but you get the sense that even though technology has progressed markedly—though “progress” isn’t the right word—her timeline is right around the corner. The hums, which have hoovered up both blue- and white-collar work alike, proliferated like mad once perfected, the same as smartphones after the iPhone or cars after the Model T. Speaking of automobiles, driverless vehicles (called “vees”) have also been developed, able to promptly deliver you to your destination for a fair sum, a ride that’s cheaper if you allow yourself to be bombarded by advertising pitches during the trip. It’s corporatocracy supercharged by the increasingly intelligent technology.

We may be witnessing the birth of a fertile, new literary subgenre.

What’s also developed at a breakneck pace is the effect of climate change. Wildfires are everywhere, and much of the earth is scorched. The unnamed city where the family lives has air quality that ranges from bad to worse. May dedicates a portion of the surgery profits to booking a three-day trip for the family at the botanical gardens, the last place left nearby featuring greenery and wildlife. Wanting the family to unplug, she lies to the children and tells them their bunnies/computers aren’t allowed in the gardens. She likewise leaves her smartphone at home. That causes a problem when Lu and Sy get lost, and May can’t contact her unwired offspring. The hum that helps the panicked mom retrieve her kids also records the tense moments with its camera, and the footage goes viral. Almost instantly, May is shamed online by trolls and bots for not keeping her children connected. Even worse, the state begins an investigation of her parenting.

Something strange happens, though. The hum that caused the trouble visits the family at home, promising to help them out of their predicament. Is the machine just doing more sly surveillance for the state? Is it a rogue robot that broke away from its mission and developed a conscience? Or is empathy programmed into the hums? The answer to these questions isn’t clear, but there’s some degree of hope. What is certain is that even though the novel has a futuristic bent, playing out against a techno-dystopia of tomorrow that’s just about here, the fears at its heart are primordial: the anxiety of a parent not being able to bond with a child. It’s a story both old and new. The same is true of Jessamine Chan’s 2023 novel, The School for Good Mothers, another narrative about a mother in danger of losing her child to a technologically advanced surveillance state. We may be witnessing the birth of a fertile, new literary subgenre.•